[An address delivered to the Interpretation Australia (IA) National Conference in Melbourne, November 2012. It was in part fulfilment of the 2011 Georgie Waterman Award I received in Perth last November.

According to IA, "heritage interpretation is a means of communicating ideas and feelings which help people understand more about themselves and their environment."]

|

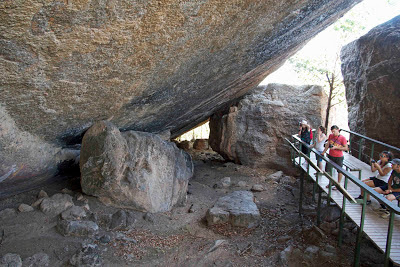

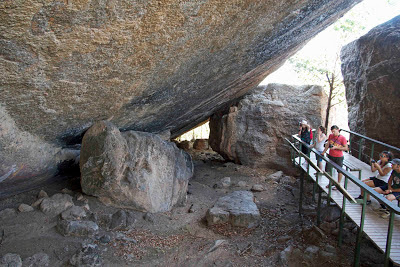

[An interpreter at work, Ubirr Rock, Northern Territory] |

Just over a century ago, a 19 year old Austrian

military cadet wrote a letter to renowned German language poet, Rainer Maria

Rilke. The young man wanted advice on how he could become a great poet. The

correspondence continued for nearly six years, and Rilke’s advice was later

published as the volume “Letters to a Young Poet”.

In Rilke’s first letter to young Franz Kappus,

he said this.

"There is only one thing you

should do. Go into yourself. Find out the reason that commands you to write;

see whether it has spread its roots into the very depths of your heart; confess

to yourself whether you would have to die if you were forbidden to write. This

most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write?

Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out in assent, if

you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple 'I must', then

build your life in accordance with this necessity; your whole life, even into

its humblest and most indifferent hour, must become a sign and witness to this

impulse."

What if we altered the above situation,

and the particular advice, and applied it to interpreters; to those who

interpret our natural and cultural heritage? If we were asked to mentor a young

interpreter, to offer advice on how someone at the start of their interpretive

career should proceed, what is it that we would say? Given what you have

learned, both obvious and profound, what might you say to help a novice

interpreter who’s itching to set foot on the long and winding road to

interpretive success?

That is the premise of my address. You, me,

we all have found – or will find – ourselves in the position of advising someone

who wants to be an interpreter. For us it’s more likely to come in the form of

an email exchange, a snatched conversation, or a meeting over coffee, but the

concept is the same. What would you put in your letters – or emails – to a

young interpreter?

One of the crucial first thoughts I had was that our young

interpreter should learn from others. I would suggest that they be a sponge;

that they listen to, watch and learn from others who have been on the road

longer. In the end I decided to apply that piece of advice to this address,

i.e. to seek the wisdom of some of our interpretation elders.

|

[Interpreting military history, Rottnest Island, WA] |

So I approached the past winners of the Georgie Waterman Award,

five interpreters whose long contribution to interpretive excellence has been

recognised by Interpretation Australia. I asked each for one paragraph, around 100 words, containing one single,

crucial lesson, reflection or piece of advice they would want to pass on to our

young interpreter. I will share their wise and generous responses with you now.

Pamela

Harmon-Price (Qld)

Pamela Harmon-Price’s advice can be

distilled into four words: “Stick to the fundamentals.” She elaborates. “Don’t

get caught up in the bells and whistles. Always try to marry the message and

medium to your audience and you are more likely to make a difference to

people’s experiences and the special places we value and want to protect.”

Pamela’s finely honed interpretive brevity comes into play again

with one closing piece of advice. “And the personal touch always works magic.”

John Pastorelli (NSW)

John Pastorelli believes that interpretation “is the key to

facilitating those experiences that become the stories we hold dear, the

stories we keep within us long after the physical journey has ended.” It can

aspire to become “the music in our hearts”, borrowing from William Wordsworth’s

poem “The Solitary Reaper”, in which the poet observes a young woman working in

a field.

Whate'er the

theme, the Maiden sang

As if her song

could have no ending;

I saw her

singing at her

work,

And o'er the

sickle bending;—

I listen'd,

motionless and

still;

And, as I

mounted up the hill,

The music in my

heart I

bore,

Long after it

was heard no more.

John suggests the young interpreter should learn to recognise

“that deeper sense of connection, meaning and story within each of us. It

happens all around us - it is the chat around a coffee table, the tears in the

backrow of the cinema, the smiles and laughs over a beer at the pub, the

solitude of a wilderness landscape. Interpretation reveals and makes personal

the richness and meaning of life. Interpretation is home.”

Robin

MacGillivray (NT)

Robin suggests that we “aim

for heartfelt, authentic interpretation that presents a variety of

perspectives, including Indigenous voices, because Indigenous

perspectives are vital - especially in Australia. Interpretation without them

is incomplete.”

She suggests the young interpreter

might achieve this by “researching the topic through those who know and care

(interviews, writings, stories, art and music), and passing on the joys the

topic gives.”

Robin warns that this will be complex, advising that we “build in the time and

money . . . that is required to do the job well. Research the pitfalls and

dance around them. The process and the product will be long lasting and beyond

expectations. The experience for the audience will be surprising and memorial.”

Gil Field (WA)

For Gil Field there is one thing so central that he says it could

well become his interpretive epitaph. “See things from your audience’s

perspectives as much as seeing the things you want to communicate.”

To do this he suggests the young interpreter should do the

following. “Ask what my audience wants (their perspective) as much as what they

need (your perspective, your intent). Then ask what it will take for them to

take the actions I want them to take? What is their mind set? What will

persuade them to see it my way and to act accordingly? You need empathy with

your audiences. You then need to talk in the language they will understand –

their language, their mind set, their perspective. It is not that hard as we

are all humans with more similarities than differences – particularly when we

are visitors to parks. We are more complex when we are members of a local

community.

So be the manager’s voice AND the audience’s ears.”

|

[Interpreting colonial heritage, Woolmers Estate, Tasmania] |

Cath Renwick (NSW)

For Cath one fundamental is to “involve people who know about lots

of different things: communication; various sciences; heritage; design;

free-choice learning - to simply ask for input/advice. It is amazing how often

people are glad to consider one's question or challenge, and respond.”

Next comes the synthesis. “If you can, take in what's offered

(even when it is a LOAD of red corrections on your finely edited copy!!) then

work out what needs to be presented to engage, provoke thought, conversations,

googling.”

“The bottom line is that ‘less is more’ when it comes to

interpretive devices and ‘more is more’ when it comes to good research,

community engagement, and evocative and accessible design.”

Of course, all interpretive projects should provide orientation,

promote exploration and make meaning, but we should also strive

to encourage participation and scaffold conversations to build

meaningful partnerships.

While it’s difficult to distill all of that wisdom into a few

words, there are some key words that our elders mention. These include some

that we would hope and expect to find: audience, research, story, fundamentals and engagement … But I also notice some other words that we might consider left-field.

Did you hear them: heart, music, dance, magic, joy, empathy? To me it is no

surprise that our elders seek to involve art alongside science, heart as well

as head. Isn’t this what Tilden meant when he called interpretation an art?

Please let me acknowledge and thank the “elders” for their

generous insights. Also let me thank our one and only Georgie Waterman

Encouragement Award winner, Jen Fry, my friend and colleague in Tasmania. It

was her suggestion that led to me contact the elders.

But I turn now to my own few paragraphs of advice. I have cunningly

allowed myself the advantage of having more that one paragraph. Still, I will

try to be brief.

* Gain first-hand experience of your subject. Get out there and

look, touch, listen, feel and even smell, whether it’s a place, an artefact or

an experience. You are doing this not

so you can tell your audience everything you have learned, but because it will

help you to appreciate, even to love,

what you interpret. And when that subtly leaks out, your interpretation will be

the better.

* Read widely, starting with actually

reading Tilden. Don’t let yourself succumb to what CS Lewis called

“chronological snobbery”, where everything new is per se better than that which is old. Yes Freeman Tilden wrote “Interpreting

Our Heritage” in 1957, and was dead before computers were part of our lives.

But wisdom is wisdom. The longer I am an interpreter, the more I come to

appreciate just how insightful Tilden was.

|

[Reading interpretive panels, Kakadu National Park, NT] |

* Feed your creative side. Take deliberate time out to do it.

Whatever it is, whether painting, writing, cooking, playing an instrument,

climbing a cliff or picking a line down a whitewater river, just do it. Even if

you do it poorly, it presents you with other challenges that will nourish you

and that part of your brain that interpretation can also tap into.

* Leave your ego at the door. You are a conduit, not the focus. This

is easier said than done, because we do all have egos. We’re interpreters after

all! And there is a place for your personality – a very important place. It adds

a unique flavour and authenticity. But it is the spice, not the meal itself.

* Be generous, collaborate, willingly share what you know and the

sources of your knowledge, with other interpreters. This is another aspect of

the ego issue. If interpretation is about audiences gaining appreciation, and

ultimately caring for that which is interpreted, then it doesn’t matter who

played what role in getting it out there.

* Don’t rely on technology alone. By all means embrace what

technology has to offer: I personally have found things like apps, blogs,

podcasts and vodcasts powerful and helpful. But in and of themselves these are

just media. To revert to an old 20th century acronym, it can be a

case of GIGO (garbage in, garbage out). As Pamela and Cath have both reminded

us, we need to get the fundamentals right first. Good content might then be

enhanced by innovative technology.

|

[Wordless interpretation, Otago Museum, Dunedin, NZ] |

* And

finally consider interpretation as a long game. Some of you may only be in the

interpretive profession for a short time. But if you become a good interpreter,

it is something that will stay with you for life, whatever your profession.

Some time in the next few years, I will probably retire from my interpretive

role with Tasmania Parks & Wildlife Service. But - and you may pity my friends and family - I fully expect that I will

be interpreting until I draw my last breath.

And if it’s a long game, then we will need patience.

Which brings me back to Rilke. Reading between the lines, it seems that the

young poet’s letters to Rilke may have been displaying impatience. In Letter 3

Rilke responds with this advice. (Again I will change “poet” to “interpreter”.)

“Being an

[interpreter] means: not numbering and counting, but ripening like a tree,

which doesn’t force its sap, and stands confidently in the storms of spring,

not afraid that afterward summer may not come. It does come. But it comes only

to those who are patient, who are there as if eternity lay before them, so

unconcernedly silent and vast. I learn it every day of my life, learn it with

pain I am grateful for: patience is everything!”