The talk will begin with words about Gustav

Weindorfer. It will celebrate his century old vision proclaimed Moses-like, arms

outstretched, from the top of Tasmania's Cradle Mountain.

"This must be a national park for the people for all time."

Within two years the Austrian, by then in his mid-thirties,

had built Waldheim – “forest home” in

English – a guest house fit for his vision. The building, or a close replica of

it, fashioned from the forest’s King Billy pines, still sits at the edge of a

forest that now bears Weindorfer’s name.

And I sit in a hut, just a stone’s throw west of Waldheim, preparing a talk about how we

might care for wild places. I am pondering the kind of life that “Dorfer”, his

wife Kate, and their many friends and guests experienced here. While we have

driven to the door in under two hours from Launceston, on their early trips they

averaged less than two miles per hour from the nearest road at Moina.

Weindorfer long lobbied successive governments to build a road in, but had very

limited success.

|

Waldheim, Cradle Mountain, Tasmania |

It is spring, so there is snow. It falls on and off

all day, by turns soft and slow; angular and sharp. We choose to walk regardless.

Pulling rain hoods tight against the wind-driven snow, we trudge, huff and crunch

our way up to Crater Lake.

In the lee of the hills the wind drops, the showers

abate, and we lower our hoods in time to enjoy the waterfalls and forest of

Crater Creek. The fagus has begun budding, and we smile at its disregard of the

snow. We spend a long while taking photographs, agreeing that we have no

schedule to keep. Is this what Gustav meant when he welcomed people here with

the words “this is Waldheim where there is no time and nothing matters”?

|

Spring thaw and fagus buds near Crater Lake |

By the time we have climbed close to Crater Lake it is

snowing steadily, softly. I wonder how many south-westerly squalls it took for

ice-age snow to accumulate here and gouge out the deep crater – really a cirque

– that is now filled by Crater Lake. But this is not the day to stay and ponder.

With visibility down to fifty metres, we cinch our hoods tight and turn back

into the cross-fire of a spectacular flurry.

|

Snow flurries at Crater Lake, Tasmania |

Gustav’s beloved Kate died tragically young in 1916. Waldheim had been her vision as much as

his. Indeed she had purchased the land on which it was built. After Kate’s

death he chose to take up permanent residence here. Although he was considered

a hermit by casual visitors, “Dorfer” was anything but. He thrived on hosting

others and showing them this special place. But with no road, and visitors

concentrated in the warmer months, he became intensely lonely, especially when

snow cut off access. He must have longed for spring and the return of warmer

weather and more frequent company.

And I wonder, really, how homely this wet forest could

ever have been. To me its soft, green-mantled, dappled light is achingly

beautiful. But it is also shady, cold and waterlogged. Even with the sun

shining, the dripping is incessant, and as I write the cold draughts finger

their way through gaps in the cabin.

|

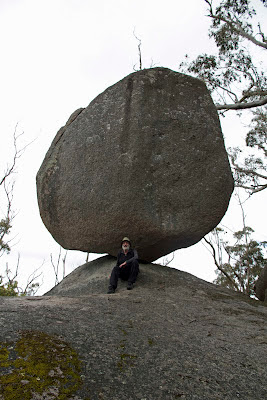

In Weindorfers Forest near Waldheim |

Clothes washing, in fact any sort of ablutions, must

have required a degree of fortitude. Just beside Waldheim, astride a fast-flowing creek, we find the old bath house.

A wooden sluice provided it with fresh – VERY

fresh – water. With snow lying on the ground, I know I would have been very

tempted to put off bath-time!

All night snow slumps from the roof, a careless

intruder stumbling into our silence. It is cold. But morning brings the gift of

a cloudless blue sky. We drive to Dove Lake after breakfast to see Gustav’s

Cradle covered in snow. Words are few – but on a day like this it would be a

hard heart that failed to share Weindorfer’s dream.

|

Cradle Mountain above Dove Lake, Tasmania |

On the drive back I look across Ronny Creek towards Waldheim. The “forest home” is at the

edge of a narrow wedge of wet forest dominated by King Billy pine and

myrtle-beech. But all around is eucalypt woodland and buttongrass moorland. Gustav’s

century old abode suddenly looks small, fragile, susceptible to changes that

are reaching even to this haven.

Am I under some kind of spell to believe that the on-going

preservation of such wild places is still possible?