|

Green Pools near Denmark, Western Australia |

Wild spring winds are a

regular part of living on Australia’s south island. Tasmania lies fair in the

path of the roaring forties, that belt of constant winds which sailing vessels

depended on for rapid movement around the globe from the 16th to

early 20th centuries. In spring these winds grow in intensity, pinched

between the still-cold southern waters and the warming continent.

But we are visiting Western

Australia. It is much drier, older and lower in latitude than our island. Its

southernmost point barely reaches 35 degrees south. We are not expecting wild

winds.

Tell that to the wind! The

day we walk in the Porongurup Range it is gusting to gale force. The range, a

smoothed over jumble of granite, is only twelve kilometres long, two kilometres

wide, and less than 700m high. As we crest the rise that leads towards Castle

Rock, a prominent knuckle of bare granite, the wind tears through the trees,

buffetting us constantly.

There’s one moment when it

rips straight off the bald rock ahead of us, bringing an unmistakably familiar

smell. I am slightly surprised to realise it’s the whiff of granite. I’d never

considered that rocks might have their own scent, but this reminds me of wind

off Mt Amos, or off any of the granitic rocks or mountains of Tasmania’s east

coast.

|

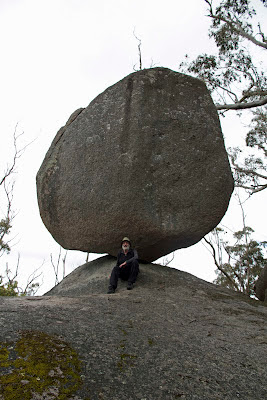

Balancing Rock (I hope!), Porongurups, W.A. (photo Lynne Grant) |

But granite is granite, with

quartz, feldspar and mica its main ingredients. And I suppose it’s that blend

of earth materials, being micro-shorn by the gale, that I am smelling. Given

that this part of the world has probably not been glaciated for millions of

years – as opposed to Tasmania’s most recent glaciation just 10-12 000 years

ago – it is wind, rain and wave action that have been the main agents of rock

weathering.

They have done a spectacular

job. The low range has no peaks to speak of, just rounded domes with the odd

egg-shaped tor. And throughout much of the south-west of Western Australia the

beaches, the soil, the predominence of sand, are in large part down to the

erosion of granite. Even the “sand groper” moniker given to Western Australians

is an outflow.

The next day we go to where

the granite meets the sea, in Torndirrup National Park near Albany. If

anything, the wind has intensified. It’s a “good” day to visit the Blow Holes,

if good means being blown off your feet and covered in sea spray.

We arrive first at the Gap

and the Natural Bridge, two granite formations resulting from the wild interactions

of rock and Southern Ocean. As we reach the carpark, the wind rocks the car fiercely.

Sea spray rises in great spumes, lashing the carpark in a salty deluge. We park

as far from the spray as we can, eschew the short but inundated track to the

Gap itself, and try to climb some boulders for a side-on view out of the spray.

I want to film and photograph, but am literally knocked off my feet.

I’m forced to crawl to the

top of a loaf-like knoll. I lie there waiting for a let-up, periodically poking

my head into the firing line. As I hug close to the rough-skinned granite, the

wind and spray are deafening. I could see it as a fine chance to converse with

the rock. I might, for instance, ask why its pink and clear crystals are so large.

It might tell me that they result from slow sub-surface cooling while it was

forming. And why, I might continue, are you so flecked with black mica, and coated

with rust and dust-coloured lichen? But then our conversation would probably be

cut short by a lull, and I’d have to “go over the top” to start filming.

At the Blow Holes the fierce

winds and waves produce another wildly spectacular show. At unpredictable intervals water is punched through

holes in the shoreline granite sending fat fountains of spray skyward before the

wind whooshes them inland, soaking unwary wave watchers.

Earlier in the week we’d

visited altogether calmer waterways, with lichen-daubed granite slabs dipping gently

down into shallow, sandy pools. And we’d spent peaceful days in a house built

around, against and seemingly at total peace with granite.

One ancient rock even allowed a karri tree to kiss it. Such are the many humours of granite.

|

Karri kissing granite xx |

One ancient rock even allowed a karri tree to kiss it. Such are the many humours of granite.

No comments:

Post a Comment